2e

アンフォルメルと東洋

Art Informel and the East

【本文確定】

アンフォルメル旋風は日本画界にも及びました。たとえば堂本印象や児玉希望ら、日本画の最高権威である日展日本画部の重鎮たちまでもが、抽象絵画の様式を当時試みました。それゆえ堂本印象とその画塾はミシェル・タピエに「日本画の最前衛」と称揚されましたが、反対に児玉希望は、抽象絵画に見える自作を具象絵画であると強弁しました。革新を謳う前衛性よりも、伝統を担う後衛性こそが、保守反動を出自とする日本画の権威の拠り所だったからかもしれません*2e1。それゆえ三上誠や不動茂弥ほか、日展に反旗を翻したパンリアル美術協会の日本画家たちのほうが*2e2、日本画のしがらみから離れ、より自由な表現を追求することができました。

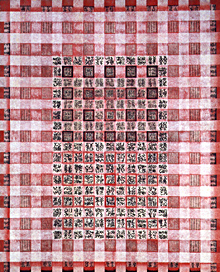

日本の書道とアンフォルメルの関係はもっと密接でした。1951年に書家の森田子龍が創刊した『墨美』第1号には二つの特集が載せられ、一つは「書道五十年史」でしたが、もう一つはアメリカ抽象表現主義の画家フランツ・クラインの紹介でした。たしかにフランツ・クラインの作品は、字体を崩し始めた日本の前衛書道に外見が似ていました。一方、アンフォルメル絵画に外見が似ていた森田子龍の作品は、早くからミシェル・タピエの関心を喚んでいました*2e3 *2e4。互いの類似に気づいた欧米のアンフォルメル画家たちと日本の前衛書家たちとの間には双方向的な影響関係が生まれ、それは、日本美術界に起きたアンフォルメル旋風においても注目されました。すなわち書道という東洋の伝統と、アンフォルメルという西洋の現代との間に関連性を指摘することが、日本の画家たちにとっては、アンフォルメルの追求を異文化への追随でなく自文化の継承であると正当化する口実となったのでした*2e5。

「アンフォルメルをめぐって」と題された1957年の『美術手帖』の誌上座談会には、「西洋と東洋・伝統と現代」という副題が添えられました。当時の関心が如実に顕れていたといえるでしょう。

The art informel sensation penetrated into the art circles of Japanese-style painting too. DOMOTO Insho 堂本印象 or KODAMA Kibo 児玉希望 for example, even such celebrated painters of the Japanese-style painting section of the NITTEN Exhibition, the highest authority of the Japanese-style painting, had once adopted the style of abstract paintings. By so doing DOMOTO Insho 堂本印象 and his school were praised as "the foremost avant-garde of Japanese-style painting" by Michel Tapie, while KODAMA Kibo 児玉希望, in contrast, insisted that his apparently abstract paintings were figurative paintings. Perhaps it was because Japanese-style painting that emerged out of reactional conservatism might seek the source of their authority in the rear guard to shoulder the traditions rather than the avant-garde to proclaim the revolution*2e1. Therefore, it was painters having departed against the NITTEN Exhibition for Pan Real Art Association*2e2, such as MIKAMI Makoto 三上誠 or FUDO Shigeya 不動茂弥, who could avoid restraints of the Japanese-style painting and pursue much freer expressions.

The relationship between Japanese calligraphy and the art informel was even closer. The first issue of the journal "Bokubi," which the calligrapher MORITA Shiryu 森田子龍 started in 1951, featured Franz Klein as well as "History of Calligraphy Over 50 Years." Indeed works of Franz Klein resembled those of the avant-garde Japanese calligraphy that had started deforming characters. On the other hand, works of MORITA Shiryu 森田子龍 that resembled those of the art informel had caught Michel Tapie's interest from its early days*2e3 *2e4. The art informel artists in Europe and America and the avant-garde calligraphers in Japan, having discovered each other's resembalances, came to develop mutually influencing relationship, which was also highlighted at the time of the art informel sensationin in Japanese art scenes. That is to say, pointing out the relevance between the calligraphy as the Eastern tradition and the art informel as the Western contemporaneity was to give Japanese painters a good excuse to justify their inclination to the art informel as not obeying the foreign culture but succeeding to their own culture*2e5.

In 1957, an art magazine "BIJUTSU TECHO," titling the issue "All Around the Art Informel," featured a discussion subtitled "the West and the East: the Tradition and the Modern," which well indicated the trend of interest at that time.