1c

「重い手」、レアリスム論争、岡本太郎

"Heavy Hand," Realism Controversy, Taro Okamoto

【本文確定】

戦前を引き継いだ画壇の芸術は、世界の実状に見合っていないばかりか、焦土と化した国土の荒廃、そして国民の精神的疲弊という現実からも遊離していました。むしろ当時の閉塞的状況をよく表していたのは、戦前から前衛芸術の担い手だった鶴岡政男や阿部展也らによる、トラウマをかかえた人間の肖像でした。鶴岡政男が「重い手」を描き話題となったのは、藤田嗣治が離日した1949年のことです。

ありのままに描いて現実をつかまえること、すなわちリアリズム(写実主義)に関しては、1946年から『みづゑ』『アトリエ』等の美術雑誌上で「レアリスム論争」が繰り広げられていました。共産党員評論家の林文雄や「日本美術会」の画家永井潔は、印象派以降の前衛芸術全てを否定する教条主義的な「民主主義リアリズム」を唱えましたが*1c1、その態度は1930年代にソ連で興った社会主義リアリズムに類似していました*1c2。これに対して評論家の植村鷹千代は、抽象芸術やシュルレアリスムへと発展した前衛芸術こそ主体のリアリティをとらえていると反論しました。そして評論家の土方定一は、民主主義リアリズムでも戦前の前衛芸術への回帰でもない、「また別のリアリズム」が探れないかと語りました*1c3。

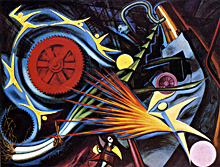

1930年代のパリでまさしく戦前の前衛芸術の渦中にいた岡本太郎は、1947年に「対極主義」を唱え、文学者や批評家をまじえて「夜の会」を結成したり、二科会内部の改革に携わったりと、旺盛な活動を開始しました。前衛芸術を抽象芸術とシュルレアリスムの対立としてとらえていた彼は、それらを弁証法的に止揚せず、対極に置いたまま提示することを目論み、さらに主題や技法、洋の東西、思想と背景、現実と理想の矛盾等、あらゆるものにその「対極」の考えを適用しました。また、今日の芸術の三原則として「うまくあってはいけない。きれいであってはならない。心地よくあってはならない」と宣言し、旧来の日本の画壇の制度はもちろん、技術偏重のリアリズムや、安易な西洋芸術の追随も一蹴し、己の絶対観でとらえた主体的な価値の創造を主張しました。

The works of postwar art circles that inherited the prewar system were not only incompatible with currents of international art but also remote from reality of the physically devastated country and the mentally exhausted nation. Rather, painters having been bearing avant-garde movements from the prewar period, such as TSURUOKA Masao (鶴岡政男) or ABE Nobuya (阿部展也), well expressed the stifling situations in portraits of traumatized people. TSURUOKA Masao (鶴岡政男) became the talk of people by executing "Heavy Hand" in 1949, the same year FUJITA Tsuguharu (藤田嗣治) left Japan.

Realism, namely attempts to capture reality by depicting it as it appears, had provoked a series of "Realism Controversy" in art magazines "Mizue," "Atlier" and others since 1946. The communist critic HAYASHI Fumio (林文雄) and the painter NAGAI Kiyoshi (永井潔) of NIHON BIJUTSU KAI embraced "Democratic Realism" that dogmatically denied all the avant-garde movements ever since Impressionism*1c1, resulting in similar attitute to that of Socialist Realism in the USSR of the 1930s*1c2. On the contrary, the critic UEMURA Takachiyo (植村鷹千代) argued that avant-garde having developed into abstract art or surrealism could better capture reality of the uncertain subject. And, the critic HIJIKATA Teiichi (土方定一) posed a question whether one could find another way to pursue realism different from either Democratic Realism or the revival of prewar avant-garde, setting off an issue later to be known as "another kind of realism"*1c3.

OKAMOTO Taro (岡本太郎), the painter who was in the midst of the heyday of prewar avant-garde movements in the 1930s' Paris, proclaimed "Bipolar Oppositionalism" in 1947 and energetically engaged in activities like assembling artists, critics and writers to organize "YORU NO KAI" (Night Meeting) or carrying out reformation of NIKA Association inside. Regarding the avant-garde as confrontation of abstract art and surrealism, he dared to present letting them stay bipolar instead of sublating them dialectically, applying the idea to any opposition such as themes and techniques, the East and the West, ideology and its surroundings, the conflict between reality and the ideal, and so on. He also declared "Should not be skillful. Should not be elegant. Should not be comfortable" as the three principles of contemporary art, rejecting initially the conventional system of Japanese art circles but also skill-oriented realism painters or easy-minded Western art followers, while calling for creation of absolute values solely following one's own subjectivity.