5c

外部: ヘタうまと日本グラフィック展

Outside: Heta-Uma and Nippon Graphic Exhibition

【本文確定】

1980年の時点では、日本の美術シーンには相異なる三つの制度がありました。(1)公募団体美術、(2)現代美術、(3)イラストレーションです*5c1。日展や二科展、あるいは日本画の院展といった「(1)公募団体美術」はサロン的アカデミズムを継承し、一般にはまだ権威があるかに見えていましたが、美術としては存在意義を希薄化してすでに久しい状況でした。次に「(2)現代美術」は、一般には「難しくてよくわからない」敬遠の対象でしたが、美術としても1970年代に実際に晦渋となってしまっていました。たとえば絵画や彫刻の形式や、具象的なイメージは、既視感を理由に自粛されていました。なお1980年以降については、美術の「内部」という言い方で前節で見たとおりです。

さて「(3)イラストレーション」とは、英語での原義は図版という意味でしかありませんが、1980年時点の日本では「商業イラストレーション」のことだったと言ってよいでしょう。イラストレーターと呼ばれる専門家が、依頼を受けて代価と引き換えに描く説明画がイラストレーションでした*5c2。つまり応用美術であり、純粋美術という意味での美術ではありません。ところが1980年以降の日本のイラストレーションは、その制度の中に「反イラスト」とでも言うべき現象を引き起こしてしまいました。依頼されてもいないのに、イラストレーションが自ら主張を始めてしまったのです。しかもこれは、ポストモダニズムと重なります。もともと近代における美術の制度が未視感を追求するためのものだったとするならば、具象イメージの復活等、既視感に関わるポストモダニズムの芸術が、美術の制度の外部で花開いたとしても不思議ではありません。それが、日本で起きたのだと私は考えます。名前は美術ではなかったとしても、その実態は明らかに「芸術のための芸術」でした。

1970年代後半、巷にはエアブラシで描いたスーパーリアル・イラストレーションがあふれていましたが*5c3、1980年頃、突如「ヘタうま」ブームが起きました。イラストレーターの湯村輝彦[テリー・ジョンスン]が東京新宿に構えるフラミンゴ・スタジオに、ぞくぞくと新しい表現を目指す若者が集まってきたのです。大塚製薬のオロナミンCのシリーズ広告や、糸井重里とのコンビによる漫画「情熱のペンギンごはん」で各界に衝撃を与えていた湯村輝彦は、(良い方から)「(1)ヘタうま、(2)ヘタヘタ、(3)うまうま、(4)うまヘタの順である」と言いました*5c4。「ヘタうま」とは「一見ヘタなようで実はうまい」という意味です。これは一見ヘタに見えるほど勢いがある、すなわち表現主義的という意味にも取れますし、玄人の技術より素人の衝動を重視するという風にも解釈できます。ヘタうまの次がヘタヘタであることから、「実はうまい」よりも「ヘタ」、すなわち「バッド」の重視が明らかでした*5c5。

メディア上での湯村輝彦一派の活躍場所は、サブカルチャー誌の『ビックリハウス』(パルコ出版)や『宝島』(JICC出版局)、あるいは業界誌『イラストレーション』(玄光社)での連載「ザ・テリータイムズ」などでした。霜田恵美子、スージィ甘金[スージー甘金]、伊藤桂司、湯村タラ、中村幸子、太田螢一、飯田三代、蛭子能収、根本敬といったニューウェーブな才能が毎号誌面をおもしろおかしく賑わし、「東京ファンキースタッフ」というグループ名で展覧会も行いました(「T・F・S展」1983年、渋谷パルコ、ほか)*5c6。

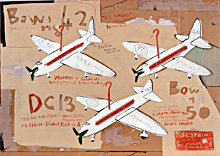

一方、パルコ主催の「日本グラフィック展」(日グラ)は、パルコのエンジンルームを率いる榎本了壱が仕掛けた公募展で、『ビックリハウス』系の姉妹誌が行った「日本パロディ展」(JPC展)を母胎としていました。応募要項には「新しい発想と表現で、イラストレーションの概念を拡張する新しいクリエーターの発掘を目指す」とあり*5c7、これにより依頼されてもいないのに描かれたイラストレーションが大挙出現することとなりました。1980年9月に開催された第1回日本グラフィック展では、応募作群はまだ「スーパーリアリズムの大襲来」状態でしたが、審査員たちが大賞に選んだのはまったく異なる伊東淳の不思議な手描き画でした*5c8。この時ぽっかりと空けられた風穴が、異変にまで発展したのは1982年の第3回展で、2,301点の応募作の大半をヘタうま的な作品が占め、どこにでも捨ててあるダンボールに落描きや切り貼りを施した日比野克彦が大賞に選ばれました。日比野克彦は一躍時代の寵児となりました*5c9。

翌1983年の第4回展では、手に手にB全パネルをかかえた応募者の長蛇の列が*5c10、受付最終日の炎天下の東京渋谷のパルコをぐるりと幾重にも取り囲みました。応募総数は主催者の予想をはるかに上回る4,634点で、出品受付は深夜になってもまだまだ終わらなかったと伝説化されています。その後も応募点数は伸び、ピークは1985年の第6回展における5,395点でした。「一見ヘタ」の気分がスーパーリアルから落描きへ、エアブラシからダンボールへ、限られた専門家から大勢の若手表現者の出現へと時代を旋回させました。大賞や上位入賞者には日比野克彦を始め、谷口康彦[谷口広樹]、田中紀之[タナカノリユキ]、伊勢克也といった東京藝術大学デザイン科の大学院生や卒業生が多く、「芸大旋風」と騒がれました。

ここに「ヘタうま-パルコ-反イラスト」という構図が見て取れます。この日本の「反イラスト」は、「バッド」な具象イメージや大勢の若手表現者の出現という欧米の新表現主義の特徴を兼ね備えていただけでなく、ポストモダニズムのもう一つの様態としてのシミュレーショニズム的な要素も垣間見せていました。湯村輝彦と湯村タラはアメリカン・フィフティーズの、霜田恵美子は大正モダン広告の、スージィ甘金は藤子不二雄とジャスパー・ジョーンズの、それぞれキッチュなパロディとも言えますし、日比野克彦の日本グラフィック展大賞受賞作は、飛行機の絵ならぬ飛行機の玩具の絵だったことから、「複製の複製的」「複々々製ぐらい」などの熱論が選評座談会で交わされています*5c11。

1985年1月、東京新宿の伊勢丹美術館では芸大旋風の担い手7名による展覧会「七福神展」が開催され、同時期に東京池袋の西武アートフォーラムとスタジオ200では、湯村輝彦一派の総勢42名による展覧会「イラストレーション・ピクニック(イラスト新鋭作家展)」が開催されました。ともに、それまでのイラストレーションの常識からは考えられない大作化や立体化が見られ、映像やライブも交えた「反イラスト」の祭典となりましたが、これを最後に保守化が起こります。国内外のニューウェーブ動向を積極的に紹介してきた『イラストレーション』誌は本来の商業イラストレーション路線に立ち返り、反対に日本グラフィック展は「アート」路線に転向しました*5c12。シミュレーショニズムという名のポストモダニズム第2波では、プレーヤーも交代します。

【初版ママ】During the latter half of the 1970s, super-real illustrations done in airbrushes were everywhere*5c1, but suddenly the "heta-uma (bad-good)" boom started to happen around 1980. Many young artists who were looking to explore new expressions in art went to Yumura Teruhiko (Terry Johnson), an illustrator who professed to be anti-high art. Yumura has already established the "heta-umai (bad-good)" style during the first half of the 1970s, and stated that the order of these designations would be "1. heta-uma (bad-good), 2. heta-heta (bad-bad), 3. uma-uma (good-good), 4. uma-heta (good-bad)*5c2." "Heta-uma" is a coined word combining the words "heta (bad)" and "umai (good)" and means works that looks bad at first glance but are actually good. This would mean that the works have vigor to an extent that they would look bad at first glance, in other words expressionism, or it would mean an approval of amateurism with emphasis on the drive to draw rather than hand technique. Because heta-heta came after heta-uma, it was clear that "heta," or "bad" was emphasized more than being "actually good"*5c3.

【初版ママ】Yumura and his school's stronghold were in such subculture magazines as "Bikkuri House" (Parco Publishing) and "Takarajima" (JICC Publishing) where artists like Shimoda Emiko, Suzy Amakane, Ito Keiji, Yumura Tara, Martin Ogisawa, Nakamura Sachiko, Ohta Keiichi and Iida Miyo made their debut*5c4. This school had a common kitsch deja vu to their works. For example, Yumura's own works had references of "heta-umai" from the American fifties, Shimoda's from Taisho modern advertisements and Amakane's from Fujiko Fujio and others' comic books for children*5c5.

【初版ママ】In the 1980s, there was the "Nippon Graphics Exhibition" which was very popular at that time organized by Parco and was a contest open to the public. It was started by Enomoto Ryoichi who headed a department called Engine Room at Parco and was part of the "Nippon Parody Exhibition" (JPC) organized by a sister publication of "Bikkuri House." The submissions that came in for the first exhibition in 1980 were mostly super-realism works with design as a premise*5c6. A sudden change occurred at the third exhibition in 1982 when much of the 2,301 submissions were heta-uma works which could not have had design as a premise. The grand prize winner was Hibino Katsuhiko's corrugated cardboard artwork and this caused a big sensation*5c7. Not only because of its graffiti touch, but the use of ubiquitous materials like corrugated cardboards which can be used for crafts had a feel of heta-uma and gave an impression of "something new" which were not design nor art from an existing context.

【初版ママ】The following year in 1983, there was a long line of applicants snaking around Koen-dori Street in Shibuya, Tokyo, where Parco is at, under the blazing sun and filled the street with B1 size (728mm x 1030mm) panels*5c8. Reception for the submissions apparently lasted until midnight. This fourth exhibition had 4,634 submissions and the sixth exhibition in 1985 had a peak of 5,395 submissions.

【初版ママ】Beginning with the grand prize winner Hibino and other top winners, many of the top prize winners were students in master's program or graduates of the design department of Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music (Geidai) and were lionized as "Geidai Sensation." Some of them included Taniguchi Yasuhiko [Hiroki], Tanaka Noriyuki and Ise Katsuya and were also followers of Yumura, but their works had a different feel compared to Yumura's straightforward kitschness and were more artistic*5c9 *5c10.

【初版ママ】In January of 1985, an exhibition of works of seven artists from the Geidai Sensation, "Seven Deities of Good Fortune" was held at Isetan Art Museum in Shinjuku, Tokyo, and at the same time, an exhibition of the works of 42 artists from the Yumura school, "Illustration Picnic (New Illustration Artists Exhibition)" was held at Seibu Art Forum and Studio 200 in Ikebukuro, Tokyo. Both exhibitions were "anti-illustration" festivals which had monumentalist and three-dimensional works as well as videos and live performances and were beyond the prevailing notion of illustration*5c11. This trend was supported by nothing other than the emergence of many unknown young artists and created an incredibly heated atmosphere.

【初版ママ】This "anti-illustration" exhibition, which is unique to Japan, flourished even more by the succession of such contest rivals as "JACA Japan Illustration Exhibiton" and "Crescent Illustration Competition" but became conservative after 1985*5c12. Seeing that works submitted to Nippon Graphics Exhibition were becoming more three-dimensional after Hibino, Parco started "Nippon Objects Exhibition" (Objects Tokyo) and made clear their direction in art. On the other hand, the magazine "Illustration" from the publisher Genkosha started a contest in the magazine called "The Choice" with one juror in 1981, and with Yumura Teruhiko as the juror for the first contest, Hibino's work was chosen and this helped to debut Hibino even before Nippon Graphics Exhibition. But when the editor-in-chief changed, a return to illustration the way it was meant to be began. During the tenure of the previous editor-in-chief Tanaka Hiroko, Ohtake Shinro, "installation," Keith Haring, Gary Panter as well as new waves from within and abroad were introduced extensively. There were also serial articles by Yokoo Tadanori and Yumura, as well as Hibino, and Murakami Takashi told me in the later years that "it was the most interesting magazine back then."